Interesting interview from a Huffington Post blog with one of the women who drove in Jeddah on October 26, 2013, by Shahla Khan Salter. A link to the story is

here, and the text is below.

On Saturday, October 26, more than 60 Saudi women got behind the wheel and drove in Saudi Arabia to

challenge the ban on women driving in that country. Some of them posted their videos on

YouTube. Several people were detained and fined.

The women were taking part in a movement, born in 1991 when

Madeha Alajaroush,

a photographer, organized a group of women and drove in a small caravan

of cars. Back in 1991, Alajaroush and her fellow activists were

criminally convicted and punished for their defiance, their lives

torn-apart by clerics.

For more than a decade activists lay low until 2008, when journalist,

Wajeha Al-Huwaider got behind the wheel and filmed herself while she drove, bravely uploading her video onto YouTube.

Then, in 2011, Al-Huwaider made another video, including a commentary

on how the driving ban impinges on the lives of Saudi woman. She

recorded it while fellow activist

Manal Al-Sharif drove on the Saudi roadway. Al-Sharif was arrested.

Following Al-Sharif's arrest, dozens of women drove in

protest after learning she was jailed for a little over a week. In 2012, Al-Sharif was named one of

Time's 100 Most Influential People. (Note: Recently, Al-Huwaider lost her appeal, her conviction of "takhbib" upheld, for helping Canadian

Nathalie Morin who remains stranded in that country with her children.)

Last week I interviewed another brave woman who drove on October 26, human rights activist and photographer,

Samia El-Moslimany.

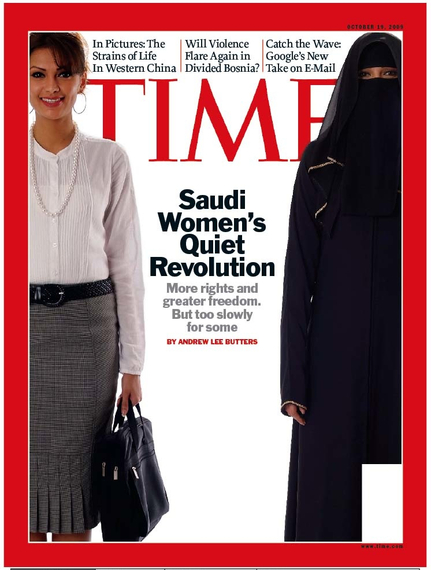

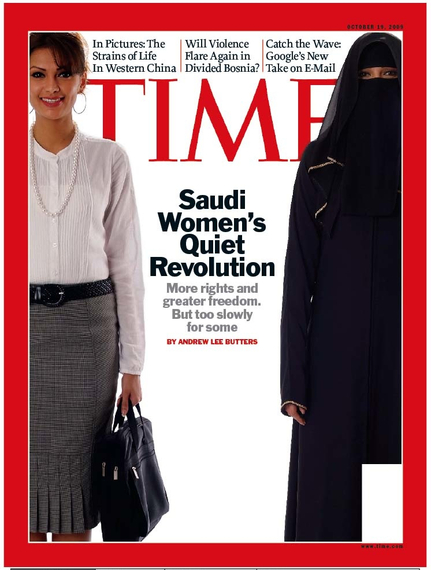

This is one of El-Moslimany's most

famous photos, published by Time Magazine.

I was joined by fellow

MPV Chile affiliate head and activist,

Vanessa Rivera de la Fuente.

Here is our inside scoop.

Samia - how do you describe yourself, how did you end up in Saudi Arabia and why do you stay?

My twitter name is

@SamiaElmo

and my description is "Samia El-Moslimany ~

Moderately-Radical-Feminist- Muslim-Saudi-American Photographer Jihading

for Peace, Love & Social Justice!"

I was born into social justice and the feminist cause. My mother and

father always lived a life of activism. I followed their path.

At 18, I fell in love with a man, in America, where I spent much of

my childhood, who seemed to be the epitome of a Muslim feminist, but who

carried a Saudi passport. We married when I was 20, despite my father's

misgivings.

We moved to Saudi Arabia from the US, hoping to invest only a few

years in Saudi Arabia, to pay off my husband's student loans. We stayed

longer because life was easy. I was embraced by my husband's extended

family, and money was good. In 1994, my husband was arrested and became a

political prisoner for nine months. We moved our family back to the US

in 2003 where we hoped to stay.

Unfortunately, our only source of work and income remained in Saudi

Arabia. Since then I split my time, commuting between my grown kids in

Seattle and my work in Saudi. My husband and I have since separated.

I am a naturalized Saudi citizen. Jeddah has been my home for 30

years. I love my extended family and friends here in Jeddah and hold a

deep Islamic conviction to work for social justice and gender equity

here.

How fast can change take place in Saudi Arabia in lifting the driving ban?

I believe that Saudi Arabia will change by evolution, not revolution.

I believe that the more women that participate -- in defiance of what

many (including some authorities) have declared is a cultural ban on

women's freedom of movement -- the more likely that those cultural

paradigms will shift.

At the beginning of the

Oct 26 campaign I decided to join and drive, and upload my

video. All Saudi women with valid drivers' licenses received from abroad were encouraged.

Were women discouraged from getting behind the wheel on October 26th?

As the day drew closer, the

Ministry of Interior warned

of consequences for women who drove and threatened that those sharing

information on social media could be charged with incitement and/or

convicted of internet crimes.

Many of my western friends married to Saudis were vocal in discouraging women, saying for example,

"it's illegal", "the country isn't ready for it", "you don't take your rights by force", "it's not our business/country" etc.

Others claimed it was an evil foreign/Western instigated campaign.

The ultra-conservative religious "right" of the country preached that it

would lead to the uninhibited mixing of the sexes, sexually immoral

behavior, the collapse of society and life as we know it, and could even

damage women's

ovaries!

Many women were discouraged. Some said it was too dangerous.

How does the inability to drive impact the average woman in Saudi Arabia?

It makes everything harder. The middle-class woman is usually able to

afford a driver. However, more often than not, having a driver is a

hassle and a hazard. Drivers are not all qualified and there are reports

of sexual abuse committed by drivers. So even with drivers, pressure is

on male family members to act as drivers for mothers, wives, daughters

and sisters.

Drivers are paid about $700/month. I estimate the average salary for

most women is usually not much more, so a driver doesn't always make

economic sense for families.

And women can't just hop on a bus. There is no transit system. There

used to be a pretty good network of inexpensive taxis, but it meant

flagging down a strange man. Now there are published reports that it is

illegal for a woman to flag a taxi. I don't know if this is enforced.

What happened on October 26th?

When October 26 dawned, I was glued to the computer. I followed

social media and posted my encouragement to those who had already

ventured out. There were no reports of arrests. In fact there was

nothing but euphoric posts of women quietly exercising their human

rights.

I asked my estranged husband to accompany me on my drive. (Women were

encouraged to have a "mahram" (guardian) accompany them. Some men did

accompany their wives while their wives defied the driving ban.) Mine declined. I then asked friends. There were no takers.

Finally, my friend,

Eva Ludemann,

a Dutch journalist, located in the Netherlands, offered to accompany me

via skype. At about 5:00 pm I taped my phone to the rear view mirror of

my car, connected with Eva and climbed into my front seat -- a

momentous occasion.

More fortunate than some women in Saudi Arabia I have a driver, Fadl

Musa Khan, who has been my companion for 27 years. He agreed to follow

me a short distance behind in another car.

We drove around the residential area of Al-Manar, in Jeddah, planning

to return after about 10 minutes. As I made a turn at an intersection, a

dusty SUV, containing two or three men, drove up alongside me.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw them scowling and waving their arms. I

continued. They followed me. Afraid, I sped up and lost them, but then

got lost myself. I tried to find my way back home. But they found me,

sped up and got between me and the car of my driver.

The back streets are isolated and I was scared. So I drove to a more

populated area. They remained on my tail. I stopped in front of a

grocery store, hopped out of my car, gestured to my driver to park. I

then climbed into the backseat and had him take over the wheel of my

car.

These men, whom I would later learn were police informants, stopped

about 25 metres away. I told my driver to stay put and we waited.

Suddenly I heard sirens. Three police cars with lights flashing sped

toward us.

I saw one of the informants climb up on the SUV and wildly wave to police. I knew immediately they were after me.

From the backseat, I instructed my driver to head for the freeway,

leaving my driver's car at the grocery store. I hoped we could lose them

in traffic. But the SUV sped up, almost colliding with us. One police

car blocked the intersection ahead of us. Another blocked us on the

right. We stopped.

A polite, uniformed officer approached the vehicle and asked for my

Saudi ID. I handed it to him with my Washington State drivers' license.

He then asked my driver for his residency permit and car registration

(and not his drivers' license).

At the intersection where we were stopped, I saw another woman

driver. She remained in her vehicle behind the wheel, veiled in a niqab

and accompanied by a boy of about 14.

The police told us all to follow them to the police station.

I asked Eva to inform both my mother, my friend and as well, women's rights activist,

Kholoud Al Fahad,

of my whereabouts. I called my attorneys, Bassim Alim and Reda

Abdulrazak. Reda advised me to sign the pledge that would be presented

to me, and to not to enter the police station without a police woman

present.

After 15 minutes of our arrival at the police station, I exited the

car and met the other woman, named Nahed Batarfi. She was also 50,

divorced, the mother of 7 and had a PhD in epidemiology. She held a

drivers' license from the UK. Since no police woman appeared, we entered

the police station together. Soon we were led to a poshly decorated

office.

A man politely questioned us (in Arabic) for hours. Here are examples of a few of the questions though not verbatim:

He said: Why were we driving?

We said: Because it is our right.

He said: What group were we part of?

We said: None, we were taking individual action, and no we didn't know each other.

He said: Who had incited us to drive?

We said: No one.

He said: Didn't we know that it is illegal for woman to drive?

We said: No, we knew that it was NOT illegal to drive, simply against the "customs" of the country.

He said: Who were our guardians?

Nahed explained she was divorced and didn't have one. I said I had

been separated for three years and refused to consider my husband my

guardian.

The Deputy Chief of Police of Jeddah then arrived. He asked the same

questions. He insisted I provide him with the contact information for my

guardian. I refused.

He said, "

in Saudi Arabia, women are queens. We respect our women not like outside the country."

I said that I alone am responsible for my own actions, and I was

insulted that a man was required to attend on my behalf. I told him that

I am 50 years old, I could be a grandmother and if I committed a crime

my guardian would not be held responsible.

The authorities said that to leave I must sign the

pledge not to drive and my estranged husband must attend to follow procedure.

They argued with me for nearly three hours. Finally, my husband

arrived. I told him I did not want him to sign anything. He stood by me

in that respect, and said he was not responsible for me, nor could he

control me. The authorities let me go though I incurred a fine. My

husband stayed. I do not know if he signed any forms.

The officer said, "

You may go. Take your car and go." And then he chuckled and wagged his finger at me, "

but let your driver drive, I don't mean YOU take your car and go!"

No women were harmed or imprisoned on October 26. Will this encourage others to get behind the wheel next time?

I hope so. It is the reason I want to share how respectful the

authorities behaved (though not the informants). I hope it will

encourage women. I signed the pledge. For now, I will not drive again in

Saudi. It is my hope that others will. If every woman who drove had to

sign a pledge that record would show the

determination of Saudi women.

Is another day planned for women to drive in protest?

The goal is to normalize driving and encourage women to drive every day. The next day of "mass" driving is

November 31.

Does this movement fall within the definition of feminism for

Saudi women? Do Saudi women view the movement from a feminist

perspective ?

Unfortunately, the term "feminism" for most Saudi women is negative,

implying atheism/secularism and anti-family, anti-Islamic behavior.

However, this movement is clearly a feminist movement.

A rose by any other name is still a rose!

Some say this struggle should not take priority in bringing

reform in Saudi Arabia because it is only a movement to help privileged

women?

Not true. Nahed, the woman who was detained with me, is not privileged.

She is educated, but is struggling as a single mother and working woman,

at the mercy of drivers and taxi cabs.

Nahed has been waiting for three months for a visa for a driver so he

can enter the country. Her 19-year-old son has been driving her and his

four sisters to school and work. Soon her son will leave to study

overseas.

Nahed drove out of desperation. It is for women like her that I drove.

The deputy police chief sympathetically listened to Nahed's plight, and gave no argument, and then turned to me and said, "

You, you have a driver, you have no excuse!"

Note: Following this interview, it was reported that on Sunday, November 3, 2013 a

Kuwaiti woman was arrested

in Saudi Arabia for driving. She was taking her elderly, sick father to

the hospital. The woman was driving in an area just over the border, in

Saudi Arabia, with her father in the passenger seat, when she was

stopped by police. Kuwaitis and Saudi citizens regularly cross the

border and communities living along the frontier are often a mix of

people from both countries. The woman is being held in custody pending

an investigation.

Follow Shahla Khan Salter on Twitter:

www.twitter.com/@MPVUmmahCanada